Joni Mitchell – Hejira | Not folk, not jazz. What is this record?

I’ve been stuck in a Joni Mitchell mode lately. It’s not a bad place to be. While I’d venture a guess that her catalog is not held in the high regard that was bestowed upon it as recently as ten years ago, those that haven’t familiarized themselves with her work have missed out on a very important time in rock history. That Mitchell has chosen to “retire” should not count against her already impressive body of work.

So we wind the Rock Chronometer back to 1976 to think of another of Mitchell’s releases that fell short of the marks set by previous and better known records – Hejira. Often mischaracterized as a jazz record, or some sort of jazz/rock/folk thing, it’s actually more of a return to form and an overt simplification following Mitchell’s true experimentations with jazz. We find the familiar elements – densely worded character sketches, highly inventive guitar work, and Mitchell’s firm grasp upon her fluid vocal range – associated with her earlier, “folkier” material. But we must set one more thing aright. Joni Mitchell was never truly a folk musician. You’d never hear her championing the power given to the masses through unionization or describing the days before and after the famine that nearly destroyed some rural village. Mitchell was more a singer/songwriter whose chosen accompaniment was acoustic guitar and piano. Her lyrical interests lie more with human interaction and the horrible and wonderful things we do to one another. Hejira’s example is further proof of the powers of this highly individualized performer.

The Asylum Records’ release begins with three jaw-dropping numbers, each a portrait of a very unique person. Mitchell’s complex poetry allows for deep examination and allows us to briefly immerse ourselves in, if not the subjects’ lives, then Mitchell’s observations of the person’s impacts on those around them. “Coyote” is the lead track and it portrays a series of events that paint the subject as often more canine or vulpine than human. He’s a scamp and a trickster, totally unscrupulous and absolutely fascinating. Mitchell breathes life into the character through a mildly enhanced acoustic guitar and the phenomenal bass work of the late Jaco Pastorius. Larry Carlton’s lead guitar work feels irrelevant as Mitchell and Pastorius move at a comfortable speed down an endless highway and past drunken kisses and stares at scrambled eggs and waitress’ legs.

The third number on the record is titled “Furry Sings The Blues,” and it’s a song attended by a minor bit of controversy from “Furry” himself. Furry Lewis was a blues musician based in Memphis, Tennessee, who was interviewed by Mitchell prior to her writing the tune. While Lewis thought nothing was to come from the conversation, he was shocked to learn that he was the subject of one of Mitchell’s songs. Hating the finished product, Lewis demanded that Mitchell pay him royalties for its use. An odd demand, true, but Lewis may actually have been offended by Mitchell’s honest portrayal of the old timer, used to highlight the faded glimmer of Beale Street and riches just out of reach against the polar opposite limousine driving past it all. Furry had a lot of reasons to sing the blues and Mitchell laid it all out for us warts (or dentures and artificial limb) and all. Mitchell is the sole guitarist on the song, but she’s backed by Carlton’s fellow L.A. Express members, bassist Max Bennett and drummer John Guerin. Neil Young adds some uncharacteristically whimsical harmonica to help recall Furry’s exciting days of yore. “Coyote” is followed by “Amelia” and a sharp change of pace. You might have guessed from the title that the song has something to do with a famous, lost aviator and you’d be right. What you couldn’t have known before listening is that Mitchell relates to Ms. Earhart in an unusual way. That Earhart disappeared before completing her last flight is seen by Mitchell as a “false alarm” – an unfulfilled dream. Mitchell equates this to her own search for love, viewing it as another false alarm or dream unfulfilled. The music’s hazy, dreamy character is courtesy of Mitchell and Carlton and their contrasting styles. Mitchell maintains a laconic strum while Carlton approximates a steel guitar. Pastorius’ absence is easily noticed, but we should trust that Mitchell feels she can best tell this story without the meandering low tones that accent Hejira’s other pieces.

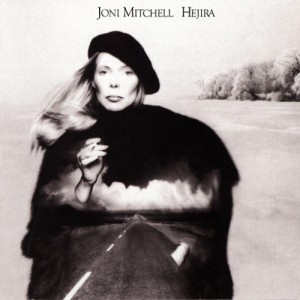

Two songs on the LP’s second side warrant some mention as well. “Black Crow,” a reunion of Mitchell, Pastorius and Carlton compares Mitchell to a crow constantly traveling in search of shiny things to pick up as she goes. The image of Mitchell as the crow is captured in the interior of the album’s gatefold jacket as Mitchell, clad in black, skates across Madison, Wisconsin’s frozen Lake Mendota. Her splayed arms, grasping for balance and with coat sleeves hanging as ragged wings is a spectacular and unforgettable image (buy the vinyl for the full effect!!). The song is upbeat and even funky. That’s no mean feat with no drummer playing behind the musicians, but Pastorius’ bobbing backbeat allows Mitchell to solidify her vision.

Finally, we’re treated to the record’s closer, “Refuge Of The Roads,” and Pastorius’ finest performance. Occasional accents are placed by trumpeter Chuck Findley and L.A. Express’ leader and saxophonist Tom Scott. While Mitchell strums along to her tale of escape through travel (one of many found in this collection), Pastorius exhibits his command of the fretless bass guitar’s upper register as a near vocal counterpoint to Mitchell’s phrasing. It leaves us on a note of melancholia and a perfect summation of Hejira’s main themes. The “Hejira,” Arabic for “journey,” definitively reveals itself as the album’s unifying concept through “Refuge”’s ruminations.

Hejira’s fantastic album cover may have intrigued many a record shopper to explore the contents inside. Those gamblers were treated to material from an artist whose commercial peak had passed, but who was at her artistic zenith. As you join me in evaluating Mitchell’s deep catalog, you’ll note that the tragedy of Hejira is that Mitchell’s journey did not lead to more compositions in the vein of those collected here. Sadly Mitchell would feel compelled to match previous successes through experiments yielding iffy results. Though not paid the same attention that she received in her youth, the bulk of Mitchell’s body of work stands the test of time, however. Hejira, for example, remains a true classic, aging much as the finest of wines and well worth your journey to acquire it.

-Mark Polzin