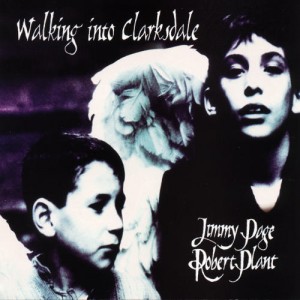

Jimmy Page and Robert Plant – Walking Into Clarksdale

Jimmy Page & Robert Plant – Walking Into Clarksdale

I can’t recall what I had going on when the main songwriters from the band Led Zeppelin, vocalist Robert Plant and guitarist Jimmy Page, decided to make an attempt at a reunion during the mid- to late ‘90s, but I was obviously not paying attention. I seem to remember a “rock radio single” or two being released, but I don’t remember hearing anything else from the duo’s only studio album of new material since the 1980 break-up of Zep, 1998’s Walking Into Clarksdale on the Mercury label. I’m not really lamenting that the reunion didn’t turn into something more full blown, as Robert Plant’s solo material in the years following has been incredible. But just what was it about this album and its live predecessor, No Quarter that held Plant’s interest briefly, but couldn’t keep him around longer? Now that I’ve just added Clarksdale to my collection, let’s see if I can’t find some answers.

Re-introducing Page and Plant to the masses begins with one of those “rock radio hits,” “Shining In The Light,” the lead track on the CD. To my ears, the song fits in well with the Zeppelin catalog, but it’s not some sort of first wave of a heavy metal onslaught. Those familiar with Zeppelin’s recordings, not just the radio hits, will know that the band had nearly as many acoustic-based numbers as they did rockers. Therefore, the acoustic guitar setting up the rest of the song does not alienate the converted, but may prevent those looking for the next “Rock and Roll” or “Black Dog” to keep on surfing. I have a quibble about the drum sound as well. While it’s next to impossible to find a percussionist that can keep to the metronomic pace set by the late John Bonham, I don’t know why the drums on this song sound as if they were played by a robot with faulty wiring. We can only blame Page and Plant, who produced the album, or Steve Albini, who engineered the thing, and we can only question their motives. We can’t fault the performer, the late Michael Lee, because I imagine that he and bassist Charlie Jones were just damned glad to be sitting in with some legends. Although the rhythm section shares songwriting credits with Page and Plant, I doubt either of the younger musicians was calling too many shots.

The other “rock radio hit” that I’d heard was the highly unusual “Most High,” which shows up as track 6 on the CD. This song is more interesting than the other single due to Page’s dark and surprising chord changes as well as the Middle Eastern instruments featured alongside the conventional rock sounds. Think of when you used to hear the song “Kashmir” on the radio, and you found it to be exotic, unnerving, and possibly a bit frightening. That same vibe is captured with “Most High.” The musicians just keep on playing, despite producing a song that may be considered to be too noisy to Western ears, and certainly unlike anything being played on the radio in The States. I don’t know if we’ve now absorbed enough elements of other world cultures that we can’t get as creeped out as we were decades ago, but “Most High” certainly does make its best attempt to unsettle the listener.

The tilted blues via The Cure that comprises the album’s title track is one more good example of how Page and Plant delight in circumventing conventions. Reminiscent of some of the start-stop cuts on Led Zeppelin’s Presence album; it demonstrates that both Page and Plant felt they had plenty of new ideas to expand upon should they continue on the reunion path. The song does beg questions, however, and these same questions likely weighed on Plant’s mind as well. Where can you take this music? Does it just keep growing and growing until the band has to tour stadiums in order to satisfy the audience? And does that happen sooner rather than later because this band consists of half of the band (and associated fame of) Led Zeppelin. With these thoughts staring Plant down, he knew that he’d have to scale everything back until he was once again performing to audiences of a size that felt more comfortable to him. With Jimmy Page sharing the bill, that was going to be impossible. You can almost hear those thoughts crossing Plant’s mind as the album wears on.

But the duo does choose to go out on a high note. The album’s last two cuts are two of the best. “House Of Love” is another one of those blues askew songs that Page seems to have in limitless supply. Again, the drums are a little annoying as they approximate an industrial rhythm, and never do start to sound organic before the song ends. But Page’s cascading changes and Plant’s exploration of his range are two elements that remind us why we’re still interested in hearing what these artists are up to after all those years. “Sons Of Freedon” gives drummer Lee the break he was waiting for, and the odd, Bonzo-esque rhythm comes blasting out. Page’s highly unconventional directions and Plant’s ramble without rhythm provide for a “Crunge”-like feel to the track, and leave us excited for anything that may follow.

Unfortunately, there was nothing to follow. All the money in the world cannot persuade Robert Plant to tour behind the Led Zeppelin banner once more. And, seriously, why would we want him to? The style of music that he performs these days is a far cry from the Caligulan excesses trotted around the globe when Led Zeppelin was at their peak. What he’s doing these days is very engaging, and certainly more heartfelt than the songs he’s being begged to sing again. I applaud him for not bowing to pressure and refusing to grab the easy paycheck.

Page and Plant’s body of work to this point stands for itself. We should be thankful that the duo was open-minded enough to give it one last go-round, and that Walking Into Clarksdale is neither an embarrassment, nor a rehash. On the right day, you might find that some of this material stands well along deep album tracks from Led Zeppelin. Yet you’ll also realize the obvious, just as did Robert Plant. You can’t try to maneuver circumstances to replicate the success reached by Led Zeppelin in the 1970s. That trick is doomed to failure. Instead, we should kick back and thank the boys for getting it right in the first place all those years ago. So few bands can even make that claim.

– Mark Polzin