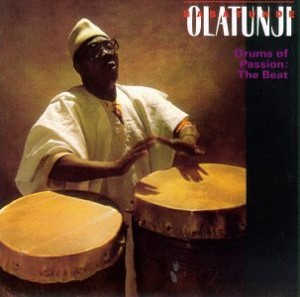

Babatunde Olatunji – Dance To The Beat Of My Drum (Drums of Passion: The Beat)

Babatunde Olatunji – Dance To The Beat Of My Drum

I know I’ve reviewed some things on this site that challenge your tasteful leanings towards the classic rock, but hang with me on this one. There’s a good story here as well as appearances by well-known artists.

How does a dude from Central Wisconsin encounter the music of a legendary African percussionist? I blame my dad. You see, dad used to really dig old Bob Dylan music. Dad likes stuff that tends towards the “folkie” side of the spectrum, and The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan is one very cool element of his collection. On that album, there’s a song called “I Shall Be Free,” which, in a typical rambling Dylan lyric, questions “what do we do about” various bald entertainers and personalities that won’t need the greasy kid’s stuff that some ad man is pushing on us. At the end of that list, almost as a cast-off, Dylan wails “Olatunji.” Now, Babatunde Olatunji was, at the time, a label mate of Dylan’s. He’d broken ground, incredibly, with his 1959 release on Columbia, Drums Of Passion, which introduced American audiences to what would later be lumped in as “world music” with his fascinating drumming and chanting. And, yes, my dad owns this record too. He’s got nothing else remotely similar in his whole library, but that’s a testament to how successful Olatunji was at breaking barriers with the power of music. Lots of people own that record, and most of them aren’t world music fans. And, in my dad’s case, he was led to it by a folkie from Minnesota.

Flash forward to 1986, and I’m working as Music Director of the local college radio station. Along with all the various “college rock” (the ridiculous term “alternative rock” hadn’t been forced on us yet) records coming into the mailbox each day (this is well before digital, kids) were an array of new blues, jazz, bluegrass, and reggae albums. Showing up one day, on the tiny San Francisco label, Blue Heron, was Dance To The Beat Of My Drum, the latest from Babatunde Olatunji. What the….? Not only that, the album was produced by Grateful Dead percussionist, Mickey Hart, and featured the guitar talents of a Mr. Carlos Santana. Double what the….? The world just got smaller and my record collection just got cooler.

1986 was probably just before I started REALLY getting into The Grateful Dead, but I was fast becoming a fan. The Dead were involved in a lot of side projects during the ‘80s, and Mickey Hart seemed to be leading a virtual percussion army! Between work with The Rhythm Devils and his Planet Drum series, Hart just about wore his hands down to nubs. But Hart understands that music is a language that transcends words, and he was happy to assemble an ensemble of over 20 musicians to help update Olatunji’s work for the modern audience. Along with San Francisco fixture Bobby Vega on bass, and legendary percussionist Airto Moreira on caxixi (pronounced “ka-SHEE-shee”, an African-Brazilian gourd-basket filled with seeds) and assistance in the production booth, the gathering set out to make BIG music and shake some cobwebs off of Olatunji’s traditional Nigerian compositions.

Olatunji was educated in The States – Atlanta and New York City, to be precise. He was well-received by hip jazz artists of the ‘50s and ‘60s and word of his prowess filtered down through the ranks of musicians in the know. Artists that incorporated Latin and African beats into their sound knew all about Olatunji. In fact, the aforementioned Santana covered one of Olatunji’s songs, “Jin-go-lo-ba”, renaming it “Jingo”, on his debut album. So now you can see how all the pieces were coming together for Dance To The Beat Of My Drum. Hart and Santana, old chums from the San Francisco psychedelic circus were very psyched for this project, as were the percussionists, who contributed Djembe, Bembe, Junjun, Agogo, Ashiko, and log drum sounds to the recording.

There are only five songs on the album, as the pieces are lengthy and give room to the percussion workouts. Olatunji’s lyrics, some in his native language and some in English lean towards spiritual concerns and folk tales. The title track, clocking in at nearly 8 minutes in length, was inspired by a friend of Olatunji’s who could simply not sit still when Olatunji began to play. While he recognized that his talents held power over acquaintances, he also knew that this story was merely one example of what he hoped his music would accomplish with listeners from around the world.

Following up is “Loyin Loyin,” which translates as “Honey Honey,” and serves as a prayer for peace for his ever-embattled homeland. The simple lyrics call for the situation in Nigeria to be sweet as honey forever. Nigeria is a complicated country, holding unbelievable oil revenue while rogue political and religious factions vie for power in the hinterlands. The clash of East and West has led to a very unique country that celebrates monetary success despite their troubles. Olatunji’s prayer seems to have gone unheard, however, as Nigeria has seen some of the worst sectarian violence in the nation’s history during the 10 years since Olatunji’s passing.

Ending side one of the album is “If? L’oju L’aiye” – a song about love. Olatunji was a big believer in universal communication and that love and rhythm were sure means of getting any message across. Evidence of this shows up on Side 2 as the drummer reprises one of his best-remembered songs from Drums Of Passion, “Akiwowo.” This time, with sizzling guitar licks from Santana spicing up the mix, the song stretches over 12 minutes, first as an a capella reading, then bringing in the full band. How is this evidence of love and rhythm being universal? Well, the song is about a legendary train conductor in Nigeria, who was adored by all passengers enjoying the introduction of a national railway system in the 1950s. How else do you explain that Americans are somewhat familiar with a train conductor from decades ago living half-way around the world? The love that Nigerians had for Akiwowo pours out through the performance, with jubilant voices and thundering beats. You’ll hear the song and just understand – like magic.

Closing out the record is “Se Eni A Fe L’Amo – Kere Kere,” which is an old adage in the Yoruba language: You are the only one who knows the one you love, you don’t always know the one who loves you. Olatunji, in his own entries in the liner notes, explains that this adage is useful when people have disagreements. We should learn to love one another indiscriminately and practice that love throughout our lifetimes.

If, at some point while reading this story, you went out to search for Dance To The Beat Of My Drum online, you may have come up empty handed. That’s because the Blue Heron version of this release has long been out of print. But in stepped Mickey Hart to the rescue, and he’s reissued the album on his own label, renaming it Drums Of Passion: The Beat. His devotion to the project has lasted decades, beginning with writing his splendid technical notes on the original album’s sleeve and then by saving it from oblivion when issuing it himself 25 years later.

So, that’s the tale of my encounter with this spectacular album, except for one more detail showing us just how small this world actually is. As time went by, my dad got new neighbors when a charming couple purchased the house next door to his. She was born in the USA, but he was a native of Nigeria, who’d come to The States for an education, but then stayed for love. Dad and Fidel aren’t bonding over drum circles or anything like that, but I doubt dad ever thought, when he went out on a limb to purchase Drums Of Passion, that one day he’d be living next door to a fella from Nigeria who was also carrying a message of love. Who could have guessed?

– Mark Polzin