King Crimson Mark III – 1972-1974, The Return of the King

“The King Crimson in 1973-74 was not a balanced group, or perhaps it was balanced in disarray. It was sometimes frightening and not a comfortable place to be. Increasingly it needed improvisation to stay alive. But that didn’t show much in studio albums. In concerts, it stepped sideways and jumped. This team looked into the darker spaces of the psyche and reported back on what it found. The 1969 Crimscapes were bleak and written, the 1973-74 Crimscapes were darker, and mainly improvised.” – Robert Fripp, The Great Deceiver Box Set.

It was 1972 and King Crimson were again in transition. The band had finished touring on the legs of its recently released live album, Earthbound. The current lineup – guitarist Robert Fripp, bassist/vocalist Boz Burrell, saxophonist Mel Collins and drummer Ian Wallace – was in its final stages, even though it had produced just one studio album, Islands. All the members, save for Fripp, would soon leave to form the band Snape with British bluesman Alexis Korner.

Fripp would be the only remaining member from King Crimson’s original 1969, a group that produced the incalculably influential In The Court Of The Crimson King. Since then, however, Crimson had been wrought with personnel changes and struggled to find a new identity in sound and personality.

But even as the latest incarnation of Crimson melted away, Fripp was intent on forming a new King, one that could harness the band’s indefinable essence. A new identity would soon emerge, and it would dramatically transform King Crimson into one of the most innovative groups of the 1970s and beyond.

The Players

First, several changes were in order. This Crimson would have two percussionists: Jamie Muir, an imaginative improviser who took to biting blood capsules on stage and hitting every bell, block and drum in his sight; and drummer Bill Bruford, who chose to leave the-then commercially successful Yes – a band that had released three magnum opuses in a row, The Yes Album, Fragile and CloseTo The Edge – for the relatively unstable and certainly unpredictable King Crimson.

“Yes had hit big and kind of robbed the bank,” said Bruford. “Once that had been done, somehow the thrill of the chase disappears quickly – getting there is much better than arriving. I think I was really looking for a change to something that had a more minor-key feel to it. Yes was essentially a pop group with some very attractive, sunny vocal harmonies, kind of like The Beach Boys. I was looking to be in a more mysterious, more improvising kind of outfit. From where I sat, Crimson was exactly that.”

The rhythm section would be completed by a musician whom Fripp (in The Great Deceiver liners) called an “increasingly loud bass-player of staggering strength and imagination, arguably the finest young English player in his field at the time. That bassist was John Wetton.

“He was in a long tradition of singing bass players,” said Bruford of Wetton. “It was an English idea that bass players sang. He had a lovely, gutsy kind of smoky sound to his voice at that time. And also, he was the hippest bass player in town.”

After the breakup of the Islands-era Crimson, Fripp chose not to replace Collins with another horn player; instead he recruited classically trained violinist and violist David Cross, whose musical talents also extended to keyboards.

Unlike the Islands-era lineup, this new Crimson was a group of musical equals (Burrell hadn’t even played bass when he joined the band; Fripp taught him his parts note by note) who were open to any direction the music might take them. The potential was mind-boggling.

“I don’t think there were any expectations, really, because it was so experimental,” said Wetton. “We knew that we wanted to be called King Crimson. We talked about it long and hard; it could have been something different. Robert had a very convincing line about it being a continuation of a way of doing things.”

“The expectations were realistic; at the same time our ambitions were enormous. They were limitless,” Wetton continued. “We realized that with this combination of people that anything was possible, really.”

The band also enlisted Wetton’s boyhood friend Richard Palmer-James, who replaced Peter Sinfield as Crimson’s lyricist.

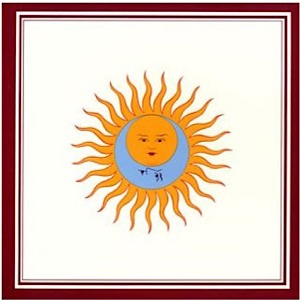

“We were at school together and have known each other since we were 12 or 13 years old,” Wetton said of Palmer-James. “We played in a band in Bournemouth together. He used to play guitar, still does. He always had a good way with words… We always kept in contact. There wasn’t really a strong point within the band, the lyrics. I suggested Richard, and everyone said let’s see what he can do. So we gave him three songs from Larks’ Tongues [In Aspic] – ‘Easy Money,’ ‘Book Of Saturday’ and ‘Exiles.’ When they came back, everyone said, “Wow! Let’s go with that.”

“As we progressed and his participation in the band became kind of more cemented and accepted, we got to interact a bit more with more him on the lyric side. There’s a point in ‘Starless’ where it’s half mine and half his. I was kind of emerging at that point,” Wetton said. “I have the utmost respect for Richard. He’s a good man, and some of his lyrics are stunning. The more you get to look into them the more you find [and think]: “You clever bastard. [laughs] I didn’t realize that the first time around.”

– Tomorrow: Writing and Rehearsals for Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, the sound and the Muir factor