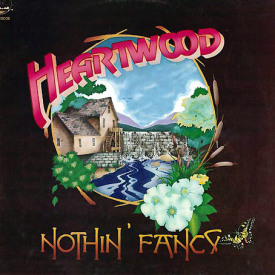

Heartwood – Robert Hudson & Tim Hildebrandt revisit “Nothin’ Fancy,” a “lost” Southern Rock belle

The 1970s were, for many, the glory days of Southern Rock. All across the south great music could be heard from bands such as The Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Outlaws, Atlanta Rhythm Section, Wet Willie, Marshall Tucker Band and many more. Of those bands that “made it,” dozens more enjoyed a run of regional popularity, soaking up the applause in back-road bars, juke joints and clubs. One such band was Heartwood, whose drummer Robert Hudson’s Web site provides the following history on the seven-piece country-rock outfit.

“Heartwood formed in Greenville, NC, in early 1972. The band was originally called The Band from Clayroot which was a little crossroads outside of Greenville. We recorded our first album in a studio in Baily, NC. It was at that time that we changed our name due to pressure from the record company that was concerned about the ‘obvious’ sexual connotation of the word clayroot. We played throughout North Carolina. Just after releasing the album, it was bought by GRC Records based in Atlanta. Their new A&R guy decided that the record should be re-recorded at their new studio in Atlanta. We went in the studio and recorded all the tracks and the ‘new’ Heartwood album was released. Our management company, also located in Atlanta started booking us in Georgia and Alabama a lot so we decided to move to Athens, GA. to be closer to our record company and the new area of gigs. Our third album, Nothin’ Fancy, was produced by Paul Hornsby who also produced all the early albums of Charlie Daniels and Marshall Tucker Band.”

Heartwood packed ’em in at Texas roadhouses and Carolina clubs, playing their blend of country-fied rock, showcasing six harmony vocalists and seven sure-footed musicians – Byron Paul (guitars/vocals), Carter Minor (harmonica/vocals/percussion), Tim Hildebrandt (guitars/vocals), Robert Hudson (drums/vocals), Gary Johnson (bass/vocals), Joe McGlohon (pedal steel guitar/alto sax/guitar) and Bill Butler (keyboards/dobra/vocals). Their musical joie de vivre runs through Nothin’ Fancy tunes such as “Lover And A Friend,” “Is It My Body Or My Breath” and “Rock N Roll Range.”

Like every band that took a couple steps toward stardom, Heartwood were dealt the inevitable blows that knocked them back and finally out of the ring for good. But that wasn’t before the release of the fine, aforementioned album Nothin’ Fancy, the recording that first brought the band to my attention. I caught up with drummer/singer Robert Hudson and guitarist/singer Tim Hildebrandt for an exclusive interview to get Heartwood’s story and learn more about Nothin’ Fancy.

I want to talk to you guys about Nothin’ Fancy overall, but I want to go back a little bit before that and get some more background. Robert, my first question is when did you start drumming and who were your influences?

Robert Hudson: Well, when I first started drumming I was probably in elementary school and I didn’t know enough about drummers to know who I was influenced by. I just knew that I wanted to play the drums. But…I’m just trying to think…I remember there were two major kind of awakenings that happened for me when I was a kid playing. And one, was a song…I was in the high school symphonic band, and we played this one tune….and I can’t really tell you too much about it but the percussion had…it was almost like a melody line… it was a part that made sense in this piece of music….so that was a real eye opener for me, because before that I’d always saw the drums as just kinda playing along and I didn’t really see it as having kind of its own voice, it was just more to play along with other people.

I remember I had my first set of drums and I had them setup in my room, I guess I was in high school at the time…. And I was listening to a – must have been a Peter Gunn album, Henry Mancini album, Peter Gunn – and I was listening to the drum part in that, and there was just this one little thing, the bongos of all things, played… and then later on in the song they repeated that same phrase but they did it in a different pitch, so it was a lower pitch, and it was the first time that this was like a… this is a musical thing and they actually, there was statements they were making and they repeat ’em, but they don’t repeat ’em the same way, they do ‘em, ya know, a little differently, and that was like….that meant a lot to me when those two things happened – that song and then marching, and then orchestra, which was really a jazz album.

But as far as drummers as I was influenced by, who would that be? Probably would have been….when I was growing up that was in the late ’50s and stuff…and so I listened to Buddy Holly and people like that and all the stuff that was on the radio so I listened to those drummers, although back then I didn’t have a clue of who they were or anything. I guess the first time I was really aware of drummers was probably The Beatles. And then…when you went to my site on my left hand side there was all those different bands I was in. And the one, the first one under drummer – the band called The Studs – what we used to do, we did a lot of Holly stuff so besides Ringo, their drummer, I really listened to him a lot and liked what he did. So, I guess those are mainly the people I really listened to. For the longest time I really shied away from listening to other drummers. In my old ego, or whatever, I thought, ya know, I needed to makeup my own parts instead of being a tape recorder and playing what other people are playing. Ya know? But in the long run I probably would have been a lot better drummer, had I not done that, had I got a lot of influences early on and then picked and chose and kind of blended those together to what I feel….

There’s a lot to be said for kind of finding your own sound, too.

Hudson: When I play, everything that I play is really is just based on what the other musicians are doing, I mean, I cannot stand to play by myself or to practice really because there is nobody to play with and I get bored really quickly. Probably the strongest thing about me is not that I’m a great technician or whatever, but I do have a good ear and I listen really well and I can follow along with most people…not jazz….but rock or folk rock or whatever, that kind of stuff. And it pretty much sounds like I know the song, playing with whoever I’m sitting in with at the time or whatever just because I do listen well. So, anyway, that’s kind of my background for drums and how I approach it.

Do you remember what your drum setup was for Nothin’ Fancy?

Hudson: You mean as far as the drum themselves? What I had and everything?

Yeah, what you were playing, what kind of drums, ya know…were you a Ludwig guy, or a Slingerland guy?

Hudson: Well, the first set of drums that I got, I got when I was in Warm. And I had them through Warm into Heartwood. And then when Heartwood…when they got us to come to Atlanta they gave us a bunch of money to buy new equipment and stuff and I wanted some Rogers drums. So, I got some oversized Rogers drums that I played through the rest of the time in Heartwood. And I’m pretty sure that I actually used my own drums in the studio as opposed to…like when we went to Nashville and did the recording, the demo recording, we just used their equipment. We used our guitars but we used their amps and their drums and all that kind of stuff. But, I’m pretty sure when we did Nothin’ Fancy I actually used my drums for that, if I remember correctly.

The first band that I was in, well, really did much in, the band called The Studs, I actually had bought a set of Rogers and I was working in a music store in Salisbury, North Carolina, where that band was from. And I bought a really nice set of Rogers drums that I really loved and I remember the guy that I worked with, he was an older guy, a jazz player, and he said, “Ya know, all the jazz players are getting 18-inch bass drums, that’s what you should get.” So, that’s what I did. But I really loved that set of drums. And then when The Studs broke up I couldn’t afford the payments anymore. So I knew this lady who was a percussionist at Catawba College, and I asked her if she wanted to take over the payments because she was a great drummer and played all kinds of stuff. And so, she said she would. So, anyway, about six or seven years ago, turns out she’s living in Chapel Hill and she now has arthritis so bad she can’t play at all. But she ended up giving those drums back to me, so I’ve still got those same set of drums that I had in 1965.

Wow. Hold on to those.

Hudson: She had played them so little they still had the original heads on them and everything. It was pretty cool.

Yeah. Roger’s kinda hold a special place in my heart because the company was based in Ohio and that’s where I grew up…Interestingly enough, Yamaha, has reintroduced that brand now. So, Rogers is back, sort of, in existence. They offer a couple entry level kits, but they’re still available now.

Hudson: Well, I know, at that point back in the late ’60s Rogers was just about the best drum on the market. And then they must have got bought out by somebody and the quality just went south. And then everybody quit buying the stuff and somebody ended up with the name obviously, but that’s cool to know that…I hadn’t heard that Yamaha was going to put that line out again. But they were really good and I still love playing those drums.

You asked about somebody who influenced me…and I don’t know how much this guy influenced me…and this wasn’t until the late ’70s but do you know Bruce Cockburn, from Canada?

He’s one my favorite songwriters.

Hudson: Well, his drummer, he had about ten albums in Canada before he ever released one in America. And the first one was that album with “Wondering Where The Lions Are.” Well, the drummer on that album was Bob DiSalle. And, he to me…had I been a really good technically great drummer I would have played like Bob DiSalle plays. I mean I’m certainly nothing like that, I’m no where near that. But he was like, to me he was like…that’s what I want to do. If I was that good, that’s what I’d be playing. So, I’d say, he’s probably the person I like the best and to some extent influenced me. But, I really like him a lot. It was cool because they were playing at NC State and I went up afterward with my son, who was maybe two at the time, and after the show was over I went up and started to talking to Bob because I really like his drumming so much. And we kind of…he was real friendly and stuff. He had a son named David, my son’s named David, both the same age and everything, we kind of got along. And we went up to a couple other gigs that they played and I talked to him again and stuff. And anyway, sometime later, maybe in the next year or two, I had a subscription to Modern Drummer Magazine. So I wrote an article to whoever there, I mean, I wrote a letter to somebody there. And I said, “ya know, there’s this drummer that I really love that you guys outta do a feature on. His name’s Bob DiSalle and he’s playing with Bruce Cockburn.” A couple months went by and I never heard anything and I kind of just forgot about it. Well, one day I’m at home in Durham…when I was living in Durham, North Carolina…and I get this phone call and danged if it isn’t Bob DiSalle. He called me and he thanked me because Modern Drummer Magazine ended up doing an article about him because of that letter that I sent. And what happened is I had a subscription and my subscription ran out and I didn’t renew it. And the very next month was the month where his article was in. and so, I went down to the local music store where they had that issue and I opened it up and it started off, “a reader in the southern part of the United States,” da da da. And that was like one of the highlights of my life, ya know, because I wrote this little letter they were doing this article on this drummer that I just thought was the best thing since sliced bread.

Very cool.

Hudson: Yeah, that was definitely a very cool thing that happened to me. But, ya know, I really like doing that kind of thing…getting people together. I’ve played with so many different people that every once in a while when I get the chance I get people together that don’t know each other because I just feel like these guys will get along well, musically, and just socially and everything, ya know? So, that’s something that I really like doing now. I’m the one who organized the whole Heartwood 25-year reunion or whatever it was, must have been 25 year reunion. Things like that. I just got back in August. I went down to Florida for about five days and The Studs had a 40-year band reunion concert that we did. And we hadn’t seen each other in forty years and it was just wonderful. It was like everybody was just the same…everybody had the same laughter, the same mannerisms and all this stuff. And nobody, basically, had seen each other in 40 years and we just had a great time. Just a great time together.

Tim, when did you first starting playing guitar and who influenced you along the way?

Tim Hildebrandt: OK, I go way back so I’m just going to probably end up dating myself. I actually started playing guitar, gosh, I actually started playing guitar professionally when I was 16 – way back when. The real influence, I guess for me, started out when Elvis Presley and them came along. And both of my parents couldn’t stand it. So, I knew there was something going for it at that point in my life. And then I learned harmony, actually singing, really, well, from the Everly Brothers. And I heard Neil Young, and I heard two guys singing and I didn’t know what harmony was at that point. And it was interesting, I knew they were doing two different things so I tried to copy both parts. So I got involved in that. Then, of course, I got in to the R&B stuff after that. It was that time of the Bobby, the Bobby Songs, I call ’em. This music was at like a dead standstill so I started following R&B stuff, ya know, black stuff. And that was great, then, of course, then The Beatles came along, and that was where I completely got mesmerized with the stuff. And…all on that route…and then… somewhere along the line in the early ’70s I saw a band outta Macon, Georgia, and they’re called Cowboy, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of ‘em?

Yeah. I’ve got one of their albums actually.

Hildebrandt: Yeah, [guitarist] Tommy Talton. They came to the show at the school I was…East Carolina University, in Greenland, North Carolina. And, I saw them, and they were doing, ya know, the country-rock thing and I thought it was great because I’d also had been involved in a lot of folk music, because when I started playing by myself I had to learn how to play finger style guitar and kinda make the sound larger. I started doing a lot of that folk music stuff. They were kind of like the bridge between folk music and country music and rock, and I thought, “This was great stuff.” And that’s pretty much where the Heartwood stuff, ya know, that influence, to start to write like that, I guess

Were you approaching the guitar then as more as more of a songwriting vehicle, or were you trying to be a lead player as well?

Hildebrandt: No, well, when I started out, it was simply a tool to write. I actually wrote my first song when I was 17 years old. I got up with a guy from North Carolina who was a song writer, which back in those days, it was not really…. a lot of people were doing it. And I kinda learned that craft, somewhat from that guy. And so I used the guitar as a tool to create songs. But I did play lead guitar in several bands. But in Heartwood I was really a guitar player and basically a songwriter, singer kinda guy. So, the guitar was a tool for a long, long time. And now, I’ve kind of come full circle with it. Actually, I’m just in the position right now, well, I’m negotiating a song I just finished writing, uh, it’s an R&B song, I do guitar solos and stuff through it. So, it kinda has gone all the way around the circle. I produced it in Nashville, had a studio there. Doing strictly like country, country rock music from like ’90…. through ’93 to ’98. And that’s where I really craft, actually crafted, songwriting skills, I think. Because it was such a competitive atmosphere there. It was like the old joke in Nashville was “How do you find a songwriter?” and the answer was, “Waiter!” They were everywhere. So, I really crafted that, and honed that skill of getting a story told in three minutes. Because in the Heartwood days, we were allowed to ramble as much as we wanted to. Ha-ha, which was fun, ya know, it was really fun.

Were you a guitar guy back then? I mean, did you have a Martin or a Gibson, or was there a guitar you lusted after? What were you playing?

Hildebrandt: Let’s see, in Heartwood actually I was a Tely-man, a Telecaster – forever. That was my first….actually, my first guitar was an Esquire. And I got mad because it doesn’t have, ya know, a pickup. So, I decided to get a Telecaster, and from then on I was pretty much a Telecaster man. When I started playing folk music I bought a brand new Martin D28 – still have it to this day – probably written 300 songs with that one guitar. And when I hit Heartwood, I started to play, actually, an Epiphone very similar to the one John Lennon used to play. I stuck with that forever through Heartwood days, and when I got out of that I strolled through the Gibson stuff, ya know, and I kept reverting back to the Fender stuff. There’s a certain sound about the guitar that can’t….I don’t care, anybody that copies one or builds one they just can’t recreate that. So, I’ve come full circle with that and I’ve got a ’51 Tely remake from the custom shop from Fender, which looks exactly like the…..I had one stolen from me…. I had a ’53 or a ’54 stolen from me many many years ago that I paid $64 for at a pawn shop in North Carolina. During the years when all the G.I.s were being sent to Vietnam and they would pawn everything they had before they went. And so I would just kinda, ya know, cruise all the pawn shops and I found a ’54…..’53, ’54, I can’t remember what it was….Tely. And it was stolen from me, so, maybe five or six years later. And when I was in Nashville, my heart just sunk because I went to a big guitar show there at the Convention Center and they had one of those there for over $70,000.

Wow.

Hildebrandt: I was going, “Wow!” Ya know.

Speaking of Nashville, have you ever been to Gruhn’s Guitars?

Hildebrandt: Oh yeah.

That’s a pretty neat place.

Hildebrandt: Yeah, I used to perform at the Bluebird Café. I don’t if you’ve heard of that.

Yep.

Hildebrandt: Like a small-weather joint. And uh, kinda scared, because when I was there, actually a guy from… most people out in the audience, of course….and this guy kept staring at me for the whole thing. And after the show, I thought, “This guy must really like the tunes or stuff.” And he said, “Where did you get your guitar?” And I said, “Well, it’s a Martin like that, from Greenville, North Carolina, in 1970…had it for so many years, and yada yada yada.” So he says, “Do you want to sell it?” I said, “No, I don’t want to sell it.” Wrote my songs with it, and he says, “Well, I’ll give you $2,000 for it.” Well, I’d originally paid $500 for it, I was like “Ehhhh, naw, I’m not really interested.” So he says, “how about $3,000?” I said, “No, no I’m not interested.” So he said, “Well, what do you do?” I said, “Well I have a recording studio here in west end of Nashville.” And he says, “Do you mind if I come by your studio and here some of your stuff?” I said, “No absolutely, come on by.” So, I didn’t think much about it and the next day he comes in….staring at my guitar. He says, “I’ll give you $5,000 for the guitar.” And this is in like ’96, and I was going “Whoa.” And I said….ya know, I gave it a second thought because I didn’t have a whole lot of money at that point. But then I said, “Ya know, I really can’t because um….ya know, there’s too much emotion involved in this particular instrument.” I had a metal guitar that I sold that I wish I had anyway. Long story short, the guy turned out he had come from Germany, he was a German guy, and he had come specifically to buy a guitar. And he was told if he wanted to buy a great acoustic guitar he went to Nashville, Tennessee and he went to Gruhn’s Guitars to buy one. That’s where he started, and then he came out to Greenville…..the guy just hounded me to death.

I don’t know if it’s your experience, but the one thing I’ve always found, particular with Martins for some reason, was they seem to get a lot better sounding the longer you have ‘em. It seems like they really need a couple years to mature and mellow to me.

Hildebrandt: Ya know, that’s right. It was funny because I can remember when I bought the guitar…it was sometime in the 1970s….but it was back in the day when guitars were actually sold, not just music stores, but like in…gosh in like jewelry stores…

Department stores…

Hildebrandt: Department stores and stuff like that. And I went into this one place and they had, I don’t know, they probably had seven or eight Martins on the wall and they were all, basically, D28s and D35s. And I played five D28s right next to each other and they all had distinctively different sounds and tones. And…..trying to take the one. And you’re right, as time has gone by it has really mellowed. And they’re big sounding guitars. Ya know, not sold early on, ya know, you don’t want to record with a Martin, you want to record with a Gibson ‘cause it was small, it will fit in the mix. And has time has gone by, that’s…kind of…not true. I do a lot of recording, engineering, and production, and I use my Martin on just about everything.

How did the seven members of Heartwood originally come together?

Hudson: Let’s see, I was in a band called Warm and then originally it was Tim. So, Tim and Bill Butler, who was a keyboard player, and Gary Johnson were playing music together. And then that band I was in, Warm, broke up. And so, we were all living in Greenville, North Carolina, at the time and I knew them. And Tim had been married to the female singer in Warm years before. So we were kind of like a family anyway. So anyway, when Warm broke up those guys asked me if I would play with them and at that time we didn’t have a record deal or anything, and as a matter of fact the band was called The Band From Clay Root because there was a little town – small little crossroads outside of Greenville called Clay Root – and that’s where two of the guys were living at the time. And so, I got together and it so was Gary and Tim, and Me and Bill. And then we decided to add a lead guitar player because Tim is a rhythm guitar player and so we didn’t really…Bill played guitar and he also played a lap steel. And anyway we decided to add a lead guitar player so we…Tim knew Byron Paul from Fayetteville – Tim had grown up in Fayetteville. So we got together with Byron and he fit in real well. And so we played for a while with that setup. And then….I’m trying to think of exactly how this went…I think the next person we added was Joe McGlohon, who was the pedal steel player, and he also played saxophone. And then we had a friend, Carter, who ended up being the harp player and singer in the band. He was a good friend of ours, and we actually hired him to be our roadie. And so he would come up during the shows and sing a song or two, and of course, he is so great, I mean he is just a great singer and a really fine harp player. And so we ended up asking him to join the band. And so that’s how the seven of us got together.

What was the common ground, musically, for you guys? I mean, to get seven people together and to agree on anything is not easy.

Hudson: Yeah. Well, ya know, we wanted to do as much original stuff as we could. And Byron and Tim – and I think actually Carter might have written a song or two – and Joe wrote a couple tunes. But we were kind of a country rock band but we weren’t really a country rock… but because we had a pedal steel everyone thought we were a country rock band. But we did sound country rock because we had the pedal steel. I don’t know, we all just kind of like that same kind of style of music and it just fit together well, and ya know, one thing led to another. And if you listen to Nothin’ Fancy and the next…what I can do if you want is I actually have Nothin’ Fancy, the album before that, which was called Heartwood, and then a demo tape that we recorded in Nashville, at a studio there, that would have been our third album had we stayed together that long. And there’s maybe eight songs on that and it’s not the greatest quality because we just recorded it live. It’s not like a produced studio album… there are other influences besides just the country rock kind of feel…there’s kind of jazzy, bluesy stuff.

Tim, had you previously worked in an outfit with so many people in it?

Hildebrandt: Not with so many people, no. No, that was the first big thing. And it was fun because it started with two. And then I hired Robert. I think it was Robert and actually he did Bill, the piano player, Bill Butler. He was next. And then we signed Byron, the lead guitar player, and got him on board. Then we signed Joe McGlohon, who turned out to be an extraordinary sax player. He became the sax player for Reba McEntire. So we just kept building people up and actually the last guy we got was Carter, the black guy. And it was funny because as soon as we hired him…hire is not a good word for it anymore. We were actually just playing, ya know, “You wanna sit in? You wanna join the band?” There was no hiring, there was no money to be offered. It was funny because, ironically, when he came on board, it was about the time when we headed for Athens, Georgia, down in that area where we live. And it was very unusual to have a black guy in the band, in an all white band.

Did that ever present any problems, particularly, since you guys primarily played in the South back then?

Hildebrandt: It did, in some cases, but it wasn’t really… it wasn’t really overt. I can only remember one occasion that that was an issue. And the occasion was we were living out, we had a big farm house out in the country and we all kinda lived in the same place, and, of course, we had to sneak Carter in because he was a black guy. And the lady in the farm house was probably 75 years old and she was brought up southern, and black people were not allowed in her houses and so forth and so on. And she came in and she saw Carter, and she kinda, her head reared back and we were like, “uh oh, we are probably going to get thrown out of this house.” And she turned around to me and she said, “Ya know, I don’t have a problem about black people, I’ve worked them all my life.” Carter and I just sat there, with our, our jaws just dropped. There was no pretense behind it, I mean, she said, “That’s just the way it is. I’ve worked them all my life.” I was like, “Whoa.” The only other sticky incidents, which became really funny is Skoots – our sound guy, our road manager – his name was Skoots Lyndon. His brother was Twiggs Lyndon, who was the road manager for the Allman Brothers. Anyway, we are eating at their house, at the Lyndon’s house, for Thanksgiving. And they invited the whole band down, so we are all sittin’ around the table and all these white people, and Carter’s, of course, standing out like a sore thumb. And we’re all sittin’ there. We’re all just sittin’ there, kinda just praying in silence. And Carter turns around to Mrs. Lyndon, Skoot’s mom, and says, “Ya know, Mrs. Lyndon, for a white lady you sure can cook.”

Ha ha ha.

Hildebrandt: Talk about breaking the ice!

Hudson: I guess we didn’t go to the really really redneck areas. I mean most of the places we played, most of ’em – the towns – were fairly big, and we never really got hassled. I know the weirdest part of the whole thing was we had gone out to L.A. and we were playing in Texas, we went out to L.A. because they had this thing called Billboard…something or other, I don’t remember what it was called but it was put on by Billboard Magazine and basically what it was for was for regional acts to play in front of a bunch of national booking agencies so people could get national booking agency deals out of the thing. So we went out there to play for that and it was weird because this one time…I guess all of us, or a bunch of us, were walking down the street, and I don’t even remember what was said but we got hassled on the streets of L.A., of all places, and we had never gotten hassled by anybody anywhere. So that was so bizarre.

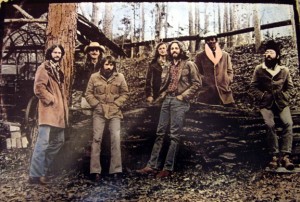

Tim, you mentioned that farm house. Is that where the picture on the back of the Nothin’ Fancy album was taken?

Hildebrandt: No. I can’t remember where that was taken. That was taken somewhere outside of Atlanta somewhere, I believe.

It looks like you’re out in the woods somewhere.

Hildebrandt: We were actually in Atlanta – outside of Atlanta. Cause we were recording at a place called The Sound Pit in Atlanta. We did all these photo shoots for that. But the house, actually, we lived in was in a place called Clay Root, North Carolina. And actually the band started as being….it was called The Dancing Clay Root before we decided… we changed the name. Real old country farm house.

So, you guys come together, seven guys, and six of you are singers, and you are in a seven piece band to begin with….Was it challenging to work in that type of a setting?

Hudson: Well, not for me. I’m not really sure what other guys would tell you. But I thought it was great, we just kind of….we played together for several years and it got to the point where you just kind of could anticipate what other people would do and I kind of gravitated towards certain parts, certain harmony parts, and other people would gravitate to other harmony parts just kind of naturally. It just kind of, I don’t know, it was pretty organic. And it just seemed to work, I mean, there were no big fights about, “oh I want this part! Or your part sucks!” Ya know? It just kind of happened.

You mentioned earlier that one of the qualities that you brought to the group was that you are a good listener and I guess one of the things that impressed me about the music too was that with seven people in the group there still seemed to be a nice sense of space in the songs, and not sort of a trampling down of instruments just because there were seven people playing.

Hudson: Sure. Well, we kind of came up…we didn’t come up with it… but we had this idea that we called it…well, I know that I’m aware of this so I think the whole band is aware of this…but we called it “focus.” And it was like, the song starts and, ya know, goes along and there’s choruses, and whatever. But it’s like, at every point in the song, there’s something that’s in focus that stands out, and all the other stuff that’s in the background or out of “focus,” back there, and everybody kind of had their chance to do that. And I mean, I guess, we were pretty good at keeping out of each other’s way so it didn’t sound like a big jumble of stuff. And that just kind of happened, we didn’t really have one person…that’s the thing that I really liked about that band…we didn’t have one person saying, “oh you gotta do this, and now you gotta play this, and now you gotta do that,” everybody kind of just added their own ideas and, to me, we were like, the group was like much greater than the sum of its parts. And just the way it kind of molded together everybody was allowed to have their own ideas, ya know, and own influences come through the music and all. And that’s the kind of band that I want to be in. Not one where there’s like a superstar who can, ya know, knock your socks off…he’s got to tell everybody what to do. It just wasn’t like that. And the bands that I’ve cared about the most have been like that…where the musicians are pretty good musicians but what we came up with was much better than any one individual musician was.

Yeah. I think that’s kind of a common thread in a lot of bands that, ya know, in many ways have stood the test of time. How would you describe the music scene in North Carolina back in the early 1970s?

Hildebrandt: Wow. It was wide open. There weren’t a lot of bands like our band…back then. There were more, um… gosh what were they? Rock and Roll, sorta Rock and Roll, I guess, is the best way to approach that. But I can remember, when we first started, I started, actually started a band with myself and uh, just a bass player, and we did like little folk songs, ya know, like a little laugh scale in the college town. And then all the other bands were, ya know, like boogie bands, ya know, rock-boogie bands. And then Robert joined us, he was the third member, I think, in the band at that point and was playing percussion and singing harmonies and so forth. And that was about the time when we got influenced by Cowboy, which was, to me, was a very unique band. For that time, they were very very unique because they were touring, ya know, like The Allman Brothers, and Grinderswitch.Ya know, that ilk. And they were all doing the same thing, and all of a sudden, here comes this group, this laid-back, ya know, they were like the precursors to… The Eagles really. The way they sounded. And we kind of styled our whole gig after that, I styled my song-writing after that. I remember my first ten or 15 songs after I saw them was like, ya know, right in their, right down their, in that vein. Because I thought I was just mesmerized by that style of music. And so it was a cool niche for us to be in. I think that was probably one of the reasons we got signed to begin with because we were out of the ordinary for that period of time. In eastern North Carolina, especially.

Were there plenty of gigs for you guys?

Hudson: Yeah. I mean, we got to the point where we didn’t really have to play…especially in Warm, I mean Warm, that band we would only play, after about a year, year and a half of being together…we got to the point where we could just play two nights a week, like Friday and Saturday, and that’s all we had to do. I mean, we certainly weren’t rich by any means, but we had enough money to live on and it was great. Just working two jobs, Friday and Saturday night, and the rest of the week was pretty much your own. I mean, we’d get together occasionally and rehearse and work up some new tunes or whatever. And Heartwood was pretty much like that, ya know, we didn’t play tons of gigs. We would play pretty much every week, a couple, two or three times and then sometimes we wouldn’t play at all. But, ya know, we played enough to pay everybody’s bills, I mean, all seven families could survive…it was a treat to go out and eat at McDonald’s…but we could pay our bills. And ya know, we got to do what we did, and we were doing what we loved by playing music. And especially once we got with the record company in Atlanta…and we went on a couple of tours, we went basically on our own, we weren’t touring with anybody, but we went on our own and it was really neat because when you go out, at least that time back then not everybody could have an album, where today anybody can by some home recording stuff and make some pretty darn good recordings. But back then, you know you go, and just because you had an album people treated you different. So, we’d tour in like Texas, or Florida, or wherever, ya know? We were out promoting the albums and stuff and it was just like because we had an album out they just treated you a little different. But, ya know, it was just nice. You’d get to a town and listen to the radio and dial in different radio stations and you’d run across one playing your song. Somebody would come out, someone from the radio station would come out and invite you out to supper and stuff like that. But it was really nice. It was a lot of hard stuff, being on the road is pretty tough. But all and all, it was a pretty good scene.

Were you guys all traveling together in one vehicle?

Hildebrandt: Yep. One vehicle. We actually had a big ol’ Suburban – Chevy Suburban – and pulled a big ol’ trailer behind that. And we had a road manager and a sound guy and they did….not all of the driving but a lot of it. But we all took our turns and it was one of those four-seaters: two air conditioners, one in the front and one in the back. I always wanted to get the very back so I could sit back there, put some headphones on. And we actually had this little….I can’t remember what that guitar thing was back then….this tiny little….Pig Nose I guess it was called.

Oh yeah, the little amp?

Hildebrandt: Yeah, you could put the headphones on and kinda zone out…write stuff.

Were you guys making any money at all?

Hildebrandt: Naw. We were kept. They [record label] paid for our homes, they paid our rent in Athens, for our houses. They kept us fed, this, that, and the other. And ya know, some money, but nothing at all, really, zero. And when I found the bill for the album, and me being a song-writer, I had signed a bunch of stuff that I shouldn’t have signed…I was just signing contract after contract. They actually called me down before we signed with that company… they flew to down to Atlanta… the president of the company took me to a concert, and he had put on the concert and The Beach Boys were the headliners and opening for The Beach Boys was a group called Mother’s Finest, which was a group out of Atlanta. And opening for them was this new guy called Bruce Springsteen. So I’m sittin’ here, here comes Bruce Springsteen, nobody had ever heard of him. And I’m sittin’ there, of course we had great seats and I’m sittin’ next to the president, and he’s wining and dining me. “Who’s that guy? Who’s that guy?” He says, “It’s Bruce Springsteen.” He’s opening for the opener. So, when I got back I remember telling Joe, cause Joe and I were living together, and I said, “Joe, I’ve seen it. I’ve seen it.” He says, “What are you talking about?” I said, “They’ve got Bruce Springsteen. You won’t believe it.” And I actually wrote the record company, I’m not sure if it was Colombia or whoever it was, in New York, and said, “This guy, does he have a record album?” He had just put out Greetings From Asbury Park. And it was still local, I mean it was still regional, wasn’t even out anywhere. And I ordered that and had it sent to me and I said, “This is the guy, this is what I’m telling you.” And of course, a couple years later – woom.

Yeah?

Hildebrandt: It was just amazing. It was the kind of thing where… so they were wining and dining me and I’m getting blown away by all of this stuff of course. So, “Sign here?” Oh yeah, I’ll sign. “What do you want me to sign?” So, I got hit for a lot of things that they were going to try to take anyway, I’ll teach some song writing and put it towards my bill and all this stuff, which had I been a lawyer it turned out, ya know, knew that they couldn’t do that kinda stuff. But that was way yonder, after the fact, after the band had broken up and I was trying to figure out what the next move was going to be.

The place where you recorded, the Sound Pit, what were the facilities like there?

Hildebrandt: It was huge. It was it.Yeah, it was it man. Way back then, it really was. It was good as any place in Los Angeles or New York. You know, brass fixtures in the saunas, steam rooms…just absolutely fantastic. In fact…..I can’t remember his name…Glenn Meadows from Nashville, Tennessee, is an engineer now, was an engineer on that album. Glenn Meadows and another guy, can’t remember…somebody else. But um, he ended up, or still is, the mastering guru in Nashville. They had some heavy hitters not only working there, but their equipment was just like, the best. It really was. We’d never really been in anything like that before. The little studio we were at before was a little thing out in like the country between Bailey, North Carolina, and Raleigh, North Carolina. It was a small…you know, egg crates on the ceiling kinda deal. The other one was acoustically designed and they had grand pianos, all kinds of… mellotrons… you know any kind of instrument you needed in the studio, huge studio.

Tell me about the label you were with out of Atlanta, GRC, and what happened to them.

Hudson: Well, that’s pretty interesting. GRC was run by Mike Thevis. Tom had called him the Porno King. He had evidently had made all his money…he was from, I think, Whiteville, North Carolina…he had made all his money by selling magazines like Playboy and stuff like that…I don’t know if it was illegal or whatever…but he made a whole bunch of money doing that kind of stuff. And then he started making movies, pornographic movies, and stuff like that. And then he decided he wanted to have a record company, so he just spent a whole bunch of money and built a great studio in Atlanta called The Sound Pit, where we recorded the Nothin’ Fancy album. And then…I’m trying to remember what happened…I think the Feds were coming down on him and so he was in this really bad motorcycle wreck…and I don’t know how real it was or if it was just something to try to get out of going to jail or whatever. But I know for a long time that kind of kept him out of jail. And about the last thing we heard…back then…and no time recently but way back then… was that he had actually gone to jail.

This guy was pretty sleazy and we were so naïve at the time. Somebody that he had some kind of a run in with, or something, had been found stuffed in the trunk of his car. You know, “Wow,” but people were just saying that kind of stuff and, of course, we were so naïve, we believed all of it. Mike’s really a good guy, he was a nice guy when we were around him. Nothing weird happened. When we were living in Greenville they said, “Well, why don’t you move down here because all your gigs are down here.” Da da da. “you’ll be close to the record company.” So we said, “OK, we’ll do that.” And then he said, “I can give you money to help you move down here.” So, the three…I think it was three wives at that time…I think we were on the road or something…and they went to meet Michael Thevis at his office in Atlanta. And we had all figured out how much money it was going to cost to move us from Greenville to Athens and I think it was like $2,300 or something, which back then was quite a bit of money in the early ’70s. Anyway, they went in there and they told him what they needed and he just pulled out this big wad of hundred dollar bills and peeled off 23, $100 dollar bills and then he said, “Well, you sure you don’t need more than that?” He was just going to give us whatever, it didn’t really matter. So they got that. So that should have told us something. This guy’s dealing with hundreds, and that’s the way they pay for everything. So that was kind of strange. But it was interesting, it was a nice studio and we got to meet…while we were recording there…there was actually a big studio and a small studio within this building, and so while we were recording our album some other people came in to record and we got to meet some of those people who were also with GRC at the time and that was neat. Plus, we got to do quite a few of opening acts when we were out promoting the album. A lot of the gigs were just us by ourselves, but every once in a while we would get an opening act and we would play with…I’m trying to think who we played with…we played with Asleep At The Wheel down in Austin…gosh, I can’t remember the guys name… a big kinda country singer now, and the name escapes me…we played with him in Fort Worth. Ya know, things like that. And that was very cool, getting to play with people who had already kind of made it and stuff. Just move up to that next level from where we had been – just playing small clubs on our own.

When your label stopped operating, I’m surprised you guys weren’t approached by another label like a Capricorn or something like that, seems like that would have been a perfect fit.

Hildebrandt: Yeah… I think it was timing. I really do. We had become disillusioned. We had started to wake up and smell the coffee as far as the label was concerned. Out in Los Angeles, the guy at the motel had actually chained our trailer to a post so we couldn’t leave because we hadn’t paid him yet and the money was supposed to be coming from the record company. It was at that point that….this was not good. So, literally, by the dark of night after the money was paid…I can’t remember if we were going from Los Angeles or maybe to San Francisco or some place else, I can’t remember where we were…somewhere on the west coast…and we hopped in the car, in the trailer everything, and high-tailed out and drove back to North Carolina.

Is that right?

Hildebrandt: We didn’t call the record company until we got to… I can’t remember…. somewhere east of the Mississippi….because we were afraid they were gonna come down on it when we just let them know that we were not doing it anymore. And that was pretty much it….and I feel to this day, I know for a fact when I was that age I had a terrible ego, ya know. And, of course, you get pampered with a lot of stuff and your ego gets bigger…junk like that. And I think to this day if we were all smart enough and pushed all our stuff behind us, we would probably still be making music together. Because it was basically all that, and the record company that everything got intertwined there… and well we just said, “Let’s just call it quits.” And you know, in hindsight, you say, you put that stuff behind you, you could probably make some pretty good money. But…it wasn’t meant to be.

Was that getting chained to the post… was that the first time that ever happened?

Hildebrandt: That was the only time that ever happened, but we were always calling, “Where’s the money? The money is supposed to be here. It’s not here,” and so forth and so on. We were pretty much a kept-band. The record company pretty much did everything. We didn’t know who paid the bills or this, that, or the other. Basically, we were naïve enough to not pay much attention to it. We were just, like I said, we were just as happy as could be to be doing it. We were at that level, we were just doing it, and having fun doing it.

Hudson: I guess it’s just as well because, ya know, we were a little scared when the band broke up. When we decided to break up the record company was none too happy when that happened. We probably owed them… I think somebody said we owed them close to $250,000. For all the recording time, for the money they loaned us, for all the advertising they did. So we were just wondering…Guido was going to show up at our door one day and take it out of our hide. Nothing like that happened, but we were a little scared there first.

Paul Hornsby produced that album. And he was just such a wonderful guy to work with, he was just amazing, I just loved working with him. And what happened is…Paul knew…he felt GRC was not promoting us nearly as well as they should have. And so he had actually talked to the people at Capricorn…as my understanding, I’ve just heard this second hand…but he supposedly talked to the people at Capricorn and talked to them about buying our contract from GRC, and for whatever reason, I don’t really know what happened, but that never did happen. But they did talk about it cause Paul liked us a lot. We got along really well and he liked our music and we really liked him and how he produced and everything but nothing came of it.

He kind of became a Southern rock legend in the producing field. What are your memories of working with him?

Hudson: Well, it’s just, ya know, he wasn’t in there…we had worked with a couple producers, this one guy especially. They had flown him in from Las Vegas and we met him at this little club called Grant’s Lounge in Macon and he was talking, he was going to produce our album. What happened is, we recorded an album called Wants and Needs in a little studio in Bailey, North Carolina. And about that time Michael Thevis…what happened actually, was one of the guys that was working with our management company was Lew Childre and his dad had been a big name in the Grand Ol’ Opry. And evidently the people at GRC wanted to sign Lew Childre. So, these people that we were working with, our management company, kind of sold us as sort of a package deal with Lew to GRC. So, anyway, so what happened is…they had a new Vice President of GRC. He came in and listened to our album and he didn’t like it. And they had already put a full page ad and billboard for this album.

OK.

Hudson: And then the next week he had pulled it all off the market and said, “We’re gonna re-record this at our studio in Atlanta.” So we went in and re-recorded it and that’s the first album, it’s just called Heartwood. So we re-recorded that at GRC and put that out. And they promoted us a little bit but not much. And things were really not happening hardly at all for us and we weren’t really sure what was going to happen. But then, a guy that was in the booking agency that was owned by the studio…somehow he knew Paul, I believe, and we were playing at a concert in Atlanta, and he invited Paul to come up from Macon and listen to the band. And Paul really liked us a lot and then it kind of went from there. And then we kind of had this revival because the record company had kind of almost kind of forgotten about us because that first album really didn’t do anything. And so, anyway, we got together with Paul and it was just like, he was able to make us sound like Heartwood instead of Heartwood-produced by Paul Hornsby, ya know? To me, it was pretty transparent, it wasn’t him, but he just helped us just do better. I’m probably not explaining that very well.

No, no, I understand.

Hudson: But, it was just that he wasn’t in there, no big egos, “No, you gotta do this, you gotta change that,” ya know? He was just very supportive and really knew how to get the best sounds out of the equipment for us and what we were trying to do. He did have the idea of us, basically, recording live in the studio, which was the way Nothin’ Fancy was recorded. And we went back and overdubbed the vocals and some lead tracks and stuff. And we did have several friends sit in with us on the album with us, and that was done. But basically, the whole band recorded the songs instead of the rhythm section, and then we’ll bring in the lead part, and then we’ll bring in the vocal parts and all that stuff. And I think that…I don’t know, I just like that approach and I think it had a good feel to the album from doing it that way.

If you can get everyone to agree to record that way, I think that that’s the best way to record because outside of playing live, how else are you really going to show your sound off?

Hudson: Yeah. And the thing about that is, I didn’t really explain it that well, its not like you go in and we’re all playing at the same time, and the drums in the drum booth, and the guitar’s in a small recording studio, ya know, 50 feet away…da da da… we were all in the same room playing live and everything was miked but it wasn’t like everybody’s separated in a small little room so there’s total separation…things would bleed from all the instruments into all the mics and that’s basically the way we recorded the rhythm part of that.

And I was just going to say…we were recording that…and the song, “Guaranteed To Win.” We had a friend of ours from Athens that we had talked to about playing banjo on it. And Paul came in and said, “I’ve got this friend that I’m doing this, this album with right now. You might want to get him to play banjo for you.” And we said, “well, no, we’ve already got our friend coming in, so we’re gonna do that.” So, anyway, he brings in this recording of…and it’s not even been mixed really…but it’s a recording of this guys band and we get to here it and it’s Charlie Daniels doing “Fire On The Mountain.”

And Charlie Daniels was the guy Paul was going to get to play the banjo. Of course, we had never heard of Charlie Daniels so we had said, “No we’re gonna get our friend from Athens to do that.”

And that would be Buddy Blackman, then?

Hudson: I’m trying to remember, there were two of them. Buddy Blackman and there was another guy who played mandolin…

There was a Buddy and a David Blackman.

Hudson: It probably says on the back of the album somewhere, I guess, what they played.

Yeah, Buddy was the banjo guy and David was the mandolin player.

Hudson: Yeah, it’s hard to remember that was so long ago. That was so long ago, that was 30-plus years ago, 33 years ago.

Tim, what are your memories of working with Hornsby?

Hildebrandt: Paul. Man, Paul was a great musician. Of course, he did all the Charlie Daniels’ stuff, Marshall Tucker. And Paul and I kind of butted heads, couple times. Another reason I said – I mean, now, this is what, a hundred years ago? – but that I can remember that I wanted to double some voices, which everybody was doing…even The Eagles… just to fill this stuff up. And he said, “Ah, we’re not gonna make any damn Carpenters records.” We didn’t do any doubling, everything was pretty much…what ya get. Paul had his way. He was strictly – you know – you get your guitar, you get your drums, and you get your bass and you play. Ya know? And you don’t do any extra “stuff.”

Would you say that there was something of a Southern rock fraternity back in those days?

Hildebrandt: Absolutely.

Was it easy to hook up and play with different people if you wanted to?

Hildebrandt: Yes it was. It was just so wide open then. There was really not a lot of pretenses. And a lot of those bands were geographically pretty close to each other. So, you’d see each other up and down the road. Of course, The Allman Brothers were obviously, ya know, the big stars and everything, at this point. But, you know, like I said, it was not unusual for Dickey Betts to sit down and jam. Or anybody, for that matter, would just come and sit in. And I can remember when we were out in Texas, Vassar Clements sat in with us, which to me, was like… he was God on the fiddle. It was funny because Bill Butler went out and played golf with him the next day. In all honestly, which I thought was pretty funny because I couldn’t picture Vassar Clements playing golf. So, I’m sure he’s not a good golfer, you know? So, it wasn’t unusual to sit in… a couple people, if I’m not mistaken from… Willie Nelson’s band… I think his sister or whoever it was used to play. It was just kind of a thing. It was small enough, of that kind of music, so that you saw each other in different situations a lot. You know, you weren’t certainly friends, and hung out with each other at all…

One thing that sets Heartwood’s sound apart from “Southern Rock Bands,” or however you want to refer to yourselves…is the heavy presence of the pedal steel guitar. Looking back now, do you think you might have had some problems with the record companies who may not have been able to label you, saying, “You know, maybe you’re too country for rock and vice versa.”?

Hudson: Well, that’s a good question, but I’m not sure I know the answer to that. I mean, we didn’t really…we only dealt with GRC so we didn’t really have any kind of talk with any other record companies to know if they would’ve thought, “Well, you guys, we want you, but you gotta get rid of the pedal steel,” or whatever. I don’t know, I guess that’s possible. I mean, country rock was pretty, kinda happening at that time. So, my guess is it probably wouldn’t have been…I mean any record company that wanted to do country rock, if they liked us, they would have picked us up. I mean, I don’t really know the answer to that. Hopefully, if that had happened we would’ve said, “Well, no, sorry, we are going to do this, and if you like it, that’s great and lets record it, but if you don’t and you want us to change it, there’s no point because that won’t be us if we change it.” So I don’t know really.

I want to talk about a couple of the songs on Nothin’ Fancy. The opening track, “Lover And A Friend,” I think is one of the best parts of the album and it sort of ends up being sort of an extended suite. It really surprised me the first time I heard it because right when you think it’s ending it’s just reaching the middle point. How did that song develop?

Hudson: Well, to me, “Lover And A Friend” will always be the quintessential Heartwood song. I mean, its just like, it took everything that we were about. More or less all the different kind of little different styles and the sounds that we had and just kind of put them together. I remember, I don’t remember exactly how that happened…I know we were playing in Auburn, Alabama, at a little club. And we were staying in this little motel and I can just remember sitting in the motel room…some people were standing around some people were sittin’ on the bed, I would’ve been sittin’ on the bed probably playing on my knees…probably just playing acoustic guitars and stuff. And that song just kind of happened, and how all those other parts came about, to tell you the truth, I don’t even know which people wrote which parts. It was just kind of an organic thing that kind of grew and, to me, that was my favorite song. I loved playing that song with that band. All those different feels and everything. It was just one of those magical things that happened. It wasn’t really planned or anything, and I’m not sure anybody was directing it to make it happen that way. That’s just what happened in that Motel room.

Yeah. That’s how it sounds…and it’s credited as a complete band composition. It sort of has that feel as if one person is picking up where the last one left off.

Hudson: Yeah, I’d forgotten about that, but yeah, I guess that’s right. I guess it was more like the whole band wrote the song as opposed to one person wrote this part, and somebody else wrote the next part. I mean, it probably was something like that. But like I said, everybody was able to add so much of themselves that even though all of the songs, basically, are written by a “writer,” I mean, we took ’em and made ’em into Heartwood as opposed to, “OK, we’ve got this Tim Hildebrandt song, let’s do a Tim Hildebrandt song.” It’s like, we took the song by Tim Hildebrandt but made into a Heartwood song because we were allowed to do that instead of, “oh you’ve gotta do it all this way, and do it all my way,” that just didn’t happen in Heartwood, which was a great thing.

Hildebrandt: The best I can recall….parts were written by different people, specifically. Actually, Byron was pretty much responsible for where we got kicked off, you know, the uptempo portion of it. The little fingerstyle thing, which I specifically wrote as a basically… was going to be another tune. And then Carter wrote the kinda bluesy thing, created that little part. We were just goofin’ around and basically, we just started breaking it down. And it was, we were really doing that, ya know, that Tommy kind of atmosphere, but in a country-rock kinda way. We were trying to have almost like a little opera deal going on. That’s how that occurred. We were all, actually, specific different people that had written different parts and we just, ya know, got in there and decided, “That would be cool to see if we could just somehow tie them all together.” And, actually, the best part about is in the end, Carter’s line, “Gonna be your lover and your friend,” and we kicked back into the top with Byron’s part, which really kinda sealed it to me.

How would you describe the different guys in the band and their contributions? You mentioned Joe – anybody who can play the pedal steel and the saxophone is a pretty incredible musician.

Hildebrandt: Well, actually, we started because Joe, ya know, learned to play a lap steel. First of all, because we wanted one. And, basically, he was playing in another band. And he sat in and played a little lap steel. And we said, “man, this is great.” So he learned his chops on the lap steel and then progressed to the pedal steel, which, to me, was amazing. The most amazing thing about his playing style, was he never played with his fingers and picks, he played with one flat pick. He did all that with a flat pick, just like you play the guitar. Absolutely mind-boggling because all the notes were so clean and so well-done when he did that. And the funny thing about the sax part, the great story about the sax part was we were sitting in the rehearsal at that big ol’ farm house I was telling you about. And we were just doing some rehearsing and so forth and so on. And I had written some tune, I don’t remember off the top of my head which one it was, but I had written some song, and we were sittin’ around chattin’ and I said, “Man, this song is dying for a sax.” And Joe said, “Well I play a little bit of saxophone.” And I said, “You do?” He said, “Yeah, I used to play it in high school, but you know, saxophone sucks.” Because he was 18 years old at this point. He says, “Saxophones are not cool…guitars are cool.” So, I said, “Just bring it to the next rehearsal and let’s just see what happens.” And he came in and played the saxophone and blew everybody away. He couldn’t just play a little sax, he could play a lot of sax. And from that time on, he was like, he was doing double duty with the band. He doesn’t play pedal steel anymore, unfortunately. Cause he had a motorcycle accident in Macon, Georgia, riding with Twiggs Lyndon and did something to his hand, tore some, I’m not sure, some nerves or something. And he can’t physically do that anymore…all the quick stuff he was doing. Well, oddly enough he did play some acoustic guitar with Reba McEntire at some point in some of the shows too. He’s pretty much an incredible musician all around. Complete all-ear, ya know.

Hudson: Joe actually ended up – after playing in bands in Richmond and wherever – he ended up being the sax player for Reba McEntire. He became just a phenomenal sax player. He’s one of those musicians that can pretty much pick up anything and play the Dickens out of it, really well, with a great touch. And that’s what he played for Reba McEntire. He was actually in the band…they were going to a gig somewhere and the band’s plane crashed and killed everybody in the band. And it’s my understanding that at the last minute Joe decided to fly with the sound crew in a different plane that day…probably because they had some great pot or something…ha ha ha. But oh man, it’s pretty amazing.

Wow. And he can’t play pedal steel anymore?

Hudson: I know that…it must have been about five to seven years ago we had a Heartwood reunion in Durham and everybody was able to come, all seven people were able to come. And Joe had borrowed a pedal steel to play, but I don’t think he had played pedal steel probably since Heartwood had broken up. He lives in Nashville now, I think. He plays with…oh what’s his name? A couple people…oh shoot, people you would know. He plays with them, he goes out and tours with them, so he’s still doing that.

What’s the deal with motorcycle accidents in Macon?

Hildebrandt: I don’t know. The thing was he was with one of the Allman Brothers people, it was strange, it was really bizarre. That would be Joe’s slant on the band as far as his musicianship. Of course, Carter came, the black guy came, completely raised on R&B stuff. The first time I heard him play the harmonica I was just….it just killed me. It was great. Because he could play a country harmonica if he wanted to but he was really deeply engrossed in the blues stuff. And when we played in Macon several times we actually had some of the Allman Brothers sit in with us and some of the Wet Willie and some of those guys. And so we would have these jams that…I can’t remember the name….this little black club, I can’t remember the name of it anymore. But I remember Carter coming in…Jimmy Hall came in. Jimmy Hall used to wear a belt…. You know Jimmy Hall? You know who I’m talking about? He’s actually the lead singer for Wet Willie.

Oh yeah.

Hildebrandt: And he played the harmonica. And he used to wear a belt, which looks like a cartridge belt, I guess. And he had his little harmonicas all around it. He’s a pretty fair harmonica player. But we showed up and Carter came in and Carter had a bandoleer. And got up there and just proceeded to blow the whole place away, and Jimmy was just sittin’ there with his mouth hanging open. It was really a fun thing. Butch Trucks was on drums, I remember, Jim was playing some percussion. Robert was playing drums, Byron, the guitar player, was playing guitar. Jimmy Hall was playing. I wanna say Dickey Betts was on the other guitar. It was some great stuff. Further along, I guess back to your original question, of course, Byron was a really young kid at that point, the lead guitar player. And I saw him, actually his brother, played bass with me years before that, his older brother. I can always remember when Bobby and I would rehearse at his house, Byron was probably only seven or eight years old.

Oh, wow.

Hildebrandt: And he was like the little brother, we’d kick him out, “Get outta here kid.” And he ends up playing guitar in the band which was really neat. I saw him at a club years later before we asked him to join the band and I went, “Whoa, look at this guy, this guy really knows his stuff.” So…Heartwood, we had a lot of…we did a lot of shtick too when we performed. We had jokes…we were a lot of like Statler Brothers’ kind of entertainment when we performed, which I wish we had a tape of that stuff because we did a lot of routines and, ya know, all kind of just beat up stuff besides just playing.

On Nothin’ Fancy, Joe’s got a couple of these short little, sorta almost like a Bob Wills-type things. Is that kind of stuff he would do up on stage? Would he improv stuff like that?

Hildebrandt: Oh, absolutely. In fact, we even did…gosh I can’t remember. It was a routine done by… Hog…shoot I can’t remember… Road Hog…Byron went through this whole thing and I was Wichita…this whole thing. And for five minutes there would be no music. And just all kind of stuff just like that. We picked up a lot of that when we went to…I guess we were in Houston, or actually Austin. We performed with Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jew Boys. And Kinky Friedman, they were major shtick. And I remember we were opening for them in Houston and I had never seen them before….they were opening for us, excuse me…and they were up there and we were getting ready to go on and we were watching them and the lead guitar player was playing with his pedals, and he was leaning back on the pedal and all of a sudden he just bellied over…just on to his back. And the whole band stopped, and I mean, everyone just takes a huge gasp in the audience. And he jumps up…ha ha ha… and starts playing… I just thought, “This is great.” And the final song was some little song about America this or America that. And the drummer has drum sticks that actually an American flag would pop out at the end, so at the end he’s waving the flag and hitting the cymbals, it was… this was good stuff here. So we did a lot of that, not as much as they did, but that was kind of one of our performances as I recall.

What can you tell me about Bill and Gary’s playing?

Hildebrandt: Bill, interestingly enough, when he started out he didn’t know anything about the dobro. And he just picked it up and he became a really sweet dobro player. And just kinda like Joe, he played piano and school but the piano wasn’t cool, ya know. He learned to play piano in piano lessons and so forth. And then he started bangin’ around on the piano and back then the country rock stuff… the piano was a lot of fill stuff… it wasn’t a lot of real heavy-duty things. And it just kind of made a really nice fit, for some reason, it just fit. But I liked his dobro playing as much as I liked anything he ever did. He had a beautiful dobro and a beautiful technique. And the tone was always so good on it. Gary was a funny guy. Gary and I went to college together and that’s where Gary and I started playing, when I was in college this where all of this started. Gary and I played together… he was roommate or, suite-mate actually at East Carolina. And Gary didn’t play an instrument at all, but he was a brilliant person, he was like a straight-A student. And I’d sit in my room across from him and just play my guitar. And he said, “I’m gonna get a bass and just kind of sit in with you.” And I thought, “Oh, well, OK, whatever.” And he didn’t really have much of an ear, but he had this incredible ability to learn stuff by kind of a numbers method.

Really?

Hildebrandt: And once you got going, he could hit every single note. It was really funny to me because he was coming from the completely opposite end of the spectrum that I was. I was coming completely from the ear… grab a guitar, make some sounds, come out of it, and go on about your business. And he was coming like almost like a writer, an old time writer, it’s like a numbers theory for him. So, that’s the way he kind of approached stuff. And of course, Robert – he’s a really fine percussionist period – and not a bad acoustic guitar player and a great harmony singer.

Yeah. You guys kind of had an unusual setup there with so many possible voices in the band.

Hildebrandt: Yeah, and that was really fun because I can remember we would start off the shows with “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” I don’t know if you know that song. But “Bonaparte’s Retreat” was basically a three-part harmony thing and we would get up there without our instruments and we would start off the thing with seven people singing it. Which was really, really, really nice. It kind of was shocking, because you open the curtains and you would think someone was going to slam out their tune and we would just be standing in front of the stage. That’s how we started our shows. It was so much fun to have seven people that could actually find a note and get in there somewhere.

Another song on here that really stands out is “Sunshine Blue,” and you had mentioned earlier about Carter’s harp playing, which I think is evident throughout this album – it’s superb. I know it’s a longer song, but was there any talk about ever making it a single, or were any of these songs considered for singles, on Nothin’ Fancy?

Hudson: Well, actually, they did put out “Home Bars And City Lights.” Which is you know, the most folky sounding song of the whole lot. Oh, that was the second single they put out. The first single they put out was “Guaranteed To Win.” That’s the one that Paul really felt should have been a hit. I mean, it’s a nice song, it’s not a great song, but it’s a nice song. He just felt, that had GRC had promoted it correctly, it could have gotten us national recognition, which of course it didn’t. So, that’s part of the reason why he wanted Capricorn to buy us because he knew that GRC wasn’t doing right by us. But the thing that I really liked is on “Satan And Savior,” Carter and Joe play harmony parts and Joe is on sax and Carter is on harp, and they sound so good together. I don’t know if you noticed that part but that’s actually saxophone and harmonica doing those two parts.

Tim, “Home Bars” and “Sunshine Blue” are both your songs. What do you remember about writing them?

Hildebrandt: “Home Bars And City Lights” was before we were getting ready to go out on tour…one of the tours. I mean, we had been on the road and we were home. And we were getting ready to go again. And I thought about all these places we had been, and so forth, and we were getting ready to go back out there again, but ya know, it’s like home bars…was not our home, but home for whoever’s town you were in. And that’s where that came from…it’s one of those kinds of songs. And it got to be, I think it was made number one in a couple towns out there in Texas. It was great because it was the first time, I remember, we pulled into some place, maybe Dallas or some place, and we turned on the radio and it was playing on the radio, which was obviously a thrill….to hear your own song on the radio. “Sunshine Blue”: Can’t be much said about it, except that it’s one of those songs where you tell your girlfriend goodbye. You’re going back on that road again.

How did Ruby Mazur come to do the album design on Nothin’ Fancy?

Hudson: Let’s see. The first album cover for Heartwood, not the Wants and Needs, but the one we re-recorded in Atlanta…the people, I think it was the graphic arts artist company from Capricorn… they were called Kitty Hawk Graphics, I believe. And they did the Heartwood album cover and I think it was the same people, I’m not positive, but I believe that it was the same people that did both of those album covers.

OK.

Hudson: Now, how they actually got up with Kitty Hawk Graphics to do the first Heartwood album cover I don’t really know. But I love that album cover. The Nothin’ Fancy cover, I think is just a great album cover….And I don’t know if it’s just me or whatever, but occasionally I’ll put that Heartwood album on, and to me, I’d like to get other people’s opinions, but to me, that album doesn’t sound all that dated like a lot of stuff. And probably the first Heartwood album would sound dated. You could say, “Oh yeah, that’s definitely from the ’70s,” or whatever. And maybe some songs on there did sound like that, but I think some of the songs don’t sound much dated at all.

Why do you think that is?

Hudson: Well, I’m not really sure I know the answer to that. But to me it’s really a nice little thing. But, of course, I don’t even know if people agree with that. But that’s just the way it feels to me when I listen to it. It just doesn’t seem all that dated.

It’s like a bunch of guys sitting around on a back porch just playing music because they love to play.

Hudson: Yeah, and I think that’s probably Paul went for us recording all in one big room…all the drums and all the amps in one room…to have that kind of feel to it. It’s just a bunch of guys that love to play getting together and playing together as opposed to, “Oh we’re going to go into a studio and see how technically advanced we can make this sound,” or whatever, ya know?

Sure. Robert, you mention on your Web site that Charlie Daniels and Toy Caldwell were going to appear on the band’s next album. Had you guys been writing or playing with them or were they just were going to kind of show up and help you?

Hudson: No, Paul would’ve produced the next album and he knew those guys and he would’ve probably talked to them about being on the next album. But we didn’t really know them or get to play with them or anything like that.

What finally broke Heartwood up?

Hudson: There was one point…we got together in Greenville and then we moved to Athens, Georgia to be close to the record company that was in Atlanta because once they started booking us and stuff most of our gigs were down in that area: Atlanta, Alabama, ya know, all in that area, so we moved down there. And at one point, I guess, we had been in Athens, maybe a year or something and people started talking, “well, lets think about moving to a different place.” And there was a neat little town up in the mountains of Georgia, I think it’s…I want to say Clayton, but I’m not sure if that’s right or not, but it’s a, anyway, a little town up in the mountains, and we liked it a lot but we kind of got the sense that maybe that wasn’t a wise move because moving up there and being a band that also had a black member, we kind of got the sense that maybe this was not too good of an idea – to move to this area. This was kind of like…dueling banjos. I mean, it was a beautiful area and all, but, so, anyway, we ended up not doing that. So we stayed in Athens and a couple of guys from the band who were from the triangle area of North Carolina, which is Durham, Raleigh, and Chapel Hill…they were really pushing hard to move back up here. So we moved back up to the Chapel Hill area, and that was in January of ’75. And then, about seven or eight months later we decided to disband. Ya know, what happens is…you play music and you are kind of on this one level, and then you kind of get this break and step up to the next level, and then you get another break and you step up to another level. Well, we had stepped up a couple levels and then it kind of just kind of just kind of stayed there. And then once that happened…the fact that we didn’t get a national book agency…that would have been the next step up. Anyway, because we kind of stayed where we were, then it kind of became a job more than what it had been before. And then we just had a meeting one day down…we were playing at this little club north of Myrtle Beach and we just started talking about it, the fact that this is not really what we wanted to do, that this is kind of just become a job. And so anyway we decided to break up, there was no…we all just agreed on it. There was no big fights or anything like that. And so we just decided to break up and that was that.

Do you think that Heartwood will play again together?

Hudson: I don’t know, I guess it’s possible that we could do another one of those reunion parties. It was really hard. We had done one, I think after ten years, and everybody was there but Joe. He wasn’t able to come. And then when we did this, I think it was 25 years, everybody was gonna be able to come but Bill Butler because he had a job that day. And at the last minute it turned out that his job was much earlier than he realized so he was able to get there. So all seven of us were there. Now, whether that would ever happen again…it was so hard to organize. I would be real surprised if that happen but it could. And the other thing is we’ve lost touch with Gary Johnson. I don’t really know where he is, if he’s still alive. He was really having a really hard time the last time we talked to him, which was at that reunion party. He was living in Cary, North Carolina, and he had been up on a ladder painting his house or something, and fell off the ladder and broke his back. And he didn’t have health insurance, so it didn’t heal right. So, from then on he was just in terrible pain all the time. And he was just really in sad shape. And then for a year or two after that party I would call him…yeah, I would call him because he didn’t do email. I’d call him and we’d talk and once in a while we’d get together and have a meal or whatever. And then several years went by and the last time I tried calling his phone number in Cary it was disconnected. So, nobody knows anything about where he is or whatever. So, I mean, I guess the rest of us could get together at some point if we could make our schedules work, I mean, I guess it’s possible. I don’t know.

Well, maybe somebody will read this and know where he is and hook you guys back up again. It’s weird the way the Internet works sometimes.