Yngwie Malmsteen interview: Sweden’s Stratocaster master

Sweden’s Yngwie Malmsteen is one of rock’s most influential and original guitarists. When most guitarists were woodshedding to copy Eddie Van Halen’s tapping technique in the late ’70s and early ’80s, Malmsteen looked much farther back for his inspiration, to the unlikely world of classical music and composers such as Antonio Vivaldi, J.S. Bach and Wolfgang Mozart. As well, the Italian virtuoso violinist Nicolò Paganini proved to be a major influence on Malmsteen’s playing and approach to his instrument. Studying such maestros, Malmsteen gained a rich harmonic palette and dazzling technique that translated amazingly well into the world of hard rock. Along the way, Malmsteen basically created the “classical metal” genre, one that’s still going strong today.

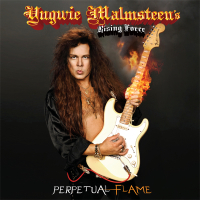

I spoke with Malmsteen recently about music, recording, his latest album, Perpetual Flame, and his Custom Tribute Fender Stratocaster.

Is it true that you first arrived in the States with only your guitar and an extra pair of pants?

[laughs] Yeah. See what happened was, I was a musician in Sweden – I started [playing when I was 5 years old – I was in bands when I was like 9 or 10. I was really, really serious, you know? By the time I was 16 or 17, I was a professional – making almost nothing, but that was what I did. When I sent the tape in to Guitar Player – I just did because they said you could do it. I didn’t expect anything. All of the sudden, the phone was ringing off the hook. At the time they called me, they said, “You’ve got to come over to America.” I said, “America? What’s that?” Because that didn’t happen to a kid from Sweden. That wasn’t the thing to do. Later on, a lot of people did that, but at that time nobody did. At the time, I had a girlfriend and a cat and a band – everything. So, I didn’t know what was going to happen. But that’s actually a true story, yeah, and that’s actually the guitar that’s on the Rising Force album.

The classical connection has always been a big part of your music. Steve Hackett has said, “The ability to be able to detach from life is something that classical music offers that rock can’t express.” Do you agree with that?

This is a really deep subject, so I’m going to elaborate if you don‘t mind. People have a very big misconception about Mozart and Bach, Beethoven and Vivaldi, and these guys. What they see now is guys in boxes playing scores. And obviously there are some superb orchestras. But you’ve got to remember that when those composers were alive, the way things were played then and composed and performed was completely different. That was today’s music. It wasn’t “classical” music then. That was that moment in time – it’s become classical now. Those guys improvised – those guys were musicians and composers and improvisers. The reason I say improvisers is because that’s a very important thing. I know a lot of people in the classical world, who play classical music today, and they cannot play an improvisation. But that’s how the great guys did it. Improvisation is the genesis of composition. If you don’t improvise, you can’t compose. If you tell most people who play in a symphony orchestra to compose something, they’ll look at you like you’re crazy. They’ll say, “I can’t compose.” They’re trained to play what’s on the paper. My sister is a classically trained musician, and you can put anything in front of her to play and she can play it – play it upside down. “Can you play this in C-sharp instead of B-minor?” She can play it no problem. But if I say, “Hey, can you improvise on this chord progression?” She probably could, but she wouldn’t want to, you know. She wouldn’t feel comfortable. I’ve done a lot of classical stuff because I’ve composed for symphony orchestras. I’ve done a lot of things where I’ve played with symphonies in Europe and Japan and China. They have one thing in common: They follow the conductor like little sheep. That’s perfect, because that’s what you’re supposed to do. It’s very, very interesting to play with those guys because they’re so good at that, you know? But that’s not the way classical music was done back in the day. Of course the ensembles had to play the written piece, but let’s say a piano concerto by Beethoven – before Beethoven went deaf, he used to perform. He would go into a cadenza for 20 minutes! He wouldn’t stop. He would improvise for 20 minutes, and then when he was done, the orchestra came in. These guys were different than most people think they were. And trust me, they’re my ultimate heroes.

You’ve got a guitar concerto under your belt now. Have you thought about writing something specifically for strings and guitar, maybe a duet or quartet piece?

Sure, sure I have. And I kind of do, because every time I compose – whether it’s for a rock band or a symphony – I do it the same way. Obviously, the orchestration is much more complex with a whole symphony. I’ve done things where I’ve re-arranged things – I do a duet for strings with my keyboard player, where I do like a Bach thing. And that’s sort of, to me, like what you’re talking about. Yeah, I do those things. To be honest with you, I’m in a place right now in my life where I really like to rock, man. [laughs]

Where does your musical inspiration come from these days?

It isn’t anything direct. It is so natural, and I swear to God that it doesn’t matter when or where – as soon as I pick the guitar up, it happens. It is composition automatic. It doesn’t stop. It’s like turning a faucet on. It’s ridiculous. And I don’t know exactly how to explain that. Sometimes I’ll come up with something, and it’s gone as quickly as it was there. If I don’t have tape running, it’s gone forever. That’s how it works for me. I don’t know how it happens, but it does.

I also write all the lyrics. And lyrics are completely different. There I draw a very strong influence from books, film, real events and feelings. My car [laughs] – whatever. So that inspiration can come from a lot of different things. But I don’t want to try to explain the music, because that’s like a magic show.

Perpetual Flame was made in sort of an old school way, refining the songs recording in between touring. What did you like about that approach?

It wasn’t by design, it’s just the way things happened. It did result in something I thought was really interesting, which is being the songwriter, the arranger, the producer – everything that I do – to come back at intervals was actually really good. To come away from it and then go back to it, I’d think, “Wow!” And you’d see it and hear it completely different, almost like an outsider. That was very good for me, because I think the album became more diverse, also more focused. Every time I came in, something appeared to me in a different way.

That’s an interesting approach, to hear your music like an outsider.

Of course, it’s not exactly like an outsider, but it’s much more so. Because first I write. Then I demo and cut the drums. Then I add the bass and guitars and keyboards. Then I write the lyrics, and then the singer comes in, then I start mixing and mastering. It’s all done in one go. You can get too close, you know.

You often call yourself a purist with regards to guitars, amps, cars and watches. What’s your feeling about analog versus digital recording?

I think, through a lot of trial and error, I realized a few things. First of all, digital recording falls and stands on one thing, which is the converters – the amount of bits and hertz that you have. At 96 kHz, 24 bits, you have very good resolution, but it seems that if you have an Apogee – if you have different converters – which it converts analog to digital and digital to analog, because ultimately what you hear is analog in the end. You have to pre-convert it… did you ever see a movie called The Fly? With Jeff Goldblum?

Yeah.

OK. It’s like that. You’re taking something, turning it into nothing and then making it into something again. That’s exactly what digital does. Whereas analog, it’s like an imprint; it’s a photograph with the sound – sound photograph on magnetic tape. Ultimately, this technology started out – I remember the first digital things, and they really sucked. It sounded like shit. It was very popular in the late ’80s for some producers to use these machines. I remember the first album I started using digital [technology] was Odyssey – that was 20 years ago. I didn’t think much about it at the time because we locked up two machines, one analog and one digital. We had two machines locked together. Then we did another album called Eclipse, which was done with digital all together – digital tape. Then after that, I was home in my own studio – I had the big reel-to-reel Studer 2-inch machines, and that’s what I stayed with for a long time. Then a friend of mine, Jeff Glixman – he’s a producer. He got me into the Otari Radar machine, which is a hard disc recorder, and I used to take the Otari and lock it up with a Studer 2-inch. I’d put them together and have the best of both worlds. It was a very good thing for a long time. When I record now, I record real, “live” drums. I don’t sample them. I don’t quantize them. I won’t sequence them. They’re real, live drums played by a real, live drummer.

What a concept.

[laughs] I like that. Yeah. Another thing: When I’m recording guitars, I have live Marshall stacks – on full! As loud as they go. And we put them in a room that’s just big enough for the walls not to be knocked out. [laughs] Yeah. I call it the “Room of Doom.” It’s an actual room with speakers, and I mike it up with some very nice AKG-442s, and I put them through a tube compressor and an equalizer-preamp, and then onto a digital hard disc recorder. And that comes out sounding like a monster, you know? Awesome.

What are the plans for your new record label, Rising Force, beyond your new album?

Well, it’s only been about a month or so. The new album, Perpetual Flame, is definitely the focal point, but there’s gonna be a lot more of my older stuff coming out. There’s gonna be some new live stuff coming out from this tour. And we’re gonna have other type of releases – books and all sorts of things. Maybe in the future, if we hear somebody really good we’ll sign them up. This is really just the beginning.

“Eleventh Hour” is one of my favorites on the new record. You recorded those strings in Istanbul?

Those guys are string guys, but I just showed them their parts – I had a guitar there – and I just said, “Here. Play, ‘dah, dah, dah, dah.’” And they had one cellist and like six violins and violas – and we double-tracked them a couple times – and it’s just so refreshing. No notes or paper. It was awesome.

You’ve said that the instrumental “Caprici Di Diablo” is the hardest thing you’ve ever played in your life. Apart from the speed of it, what makes it so challenging?

That’s a very good question. What makes it really challenging is the fact – you have A-major, a-minor, D-major, G-major. [hums chord progression] You have a chord progression that goes more than once. I left it very bare. It’s basically just a lead guitar and bass, so there’s nowhere to hide. I wanted it to be very daring, but I wanted it to be structured. I wanted to capture the moment. That was the last thing I did on the record – I kept saying, “Let’s do something else. Let’s do something else,” until there’s nothing left to do, and I had no choice. [laughs] I could go in and play it like a robot – I could play the chords, no problem. I mean, it’s physical, but I could do it. But I didn’t want that: I wanted to capture the moment – I did it pretty much in one take. I don’t like to go back and do it over and over and over, because it never gets any better.

“Live To Fight” has almost a medieval feel at the beginning and a cool groove, and the whole album has sort of an ancient vibe to it. Were you going for that?

You know, I didn’t really go for anything. It was just whatever new material came out, but coming back to it every time from a tour or something like that, I came back and it sounded really different. When it came to songs like “Live To Fight,” that’s when I decided it wasn’t going to work with the old singer. The songs were more or less totally finished when Tim [“Ripper” Owens] came in. I don’t think I had a specific idea, but it was just a natural evolution of things.

If you view the voice as an instrument, how would you describe Tim Owens?

Well, I think that he’s got the power and the range and the vibrato that I like – he’s got all those elements that I really dig, you know? And he sings all the material almost like perfect. It’s a very good match.

You changed singers in the middle of this project. It seems like you’ve had to defend yourself a lot for taking charge of your musical projects. Who knows better what you want than you?

It’s a toughie. What it is, is that I want to have the best guys to form the parts I like. I would probably have to say, even though it sounds a little pretentious, is that I work very much like a classical composer. You know in a Vivaldi concerto, the cellist doesn’t say, “Excuse me. Can I play an f-sharp here instead?” Because that’s the way it is, you know? It’s a funny thing.

Congratulations on your signature Stratocaster. Fender did an amazing job. The detail is stunning, right down to the bite marks.

Yeah. Well, imagine how I feel. They sent me one, and when someone opened the case – because I lent them the real one to copy – and I thought they had sent that one back. I swear to God, man. I’ve had that guitar for 30 years. It [the reproduction] smells the same. It’s sick. I said to [Fender master builder] John Cruz, “How did you guys do this? Is it some sort of alchemy? Is there witchcraft going on there?”

That’s quite an honor.

Oh my God. Yeah!

One of the great things about music is the passing of the torch. I’m sure a lot of today’s players were as inspired to pick up the guitar after hearing “Black Star” as you were from hearing Deep Purple’s “Fireball” or “Demon’s Eye.” That’s a cool circle to be in.

Yeah, absolutely. Not too long ago I went to see Black Sabbath in Miami – they’re called Heaven And Hell now. And I gotta tell you, man, these guys lifted the roof off the place. It was so fucking good. And you know who was opening?

Who?

Alice Cooper. He’s a good friend of mine, as well. Alice was amazing. These guys could be my dad, man. So there’s no reason to say, “OK, I’m done now,” after those shows. It was very cool, because those guys rock harder… I remember a lot of festivals here in the summer – I get to see a lot of bands. Sabbath and Alice Cooper were really rocking. So I hope I can keep it up like that, also. That’s what I want to do, anyway. [laughs]